The following is a draft for an article based on a presentation Ethan O’Connor and Brian O’Connor made at the Document Academy several years ago. It presents some thoughts on photographs as representations and some considerations of uses of photographs in archives.

Resolving the Past: Mirror Memory

Brian C. O’Connor & Ethan M. O’Connor

Abstract

We present a fundamental model of photography as a particular constraint on entropy – a document. We consider the consequences of seeing photography in this light for formal notions of representation, especially representation of cultural heritage objects. We present a case study of photographing a large piece of realia to demonstrate that it is possible to achieve a 1:1 correspondence between the visual data set presented to a human observer by the original object and the data set presented by an ultra-high resolution digital image of the object. We then examine what is left out in ordinary photographic representations. We then present research and considerations of other aspects of vision that might increase the number of circumstances under which the 1:1 correspondence would hold and might thus increase the uses to which the photographic representation could be put.

Photons In, Photons Out

Under the action of light, then, a body makes its superficial aspect potentially present at a distance, becoming appreciable as a shadow or as a picture. But remove the cause,—the body itself—and the effect is removed. The man beholdeth himself in the glass and goeth his way, and straightway both the mirror and the mirrored forget what manner of man he was. These visible films or membranous exurse of objects, which the old philosophers talked about, have no real existence, separable from their illuminated source, and perish instantly when it is withdrawn.

Oliver Wendell Holmes, “The Stereoscope and the Stereograph” Atlantic Monthly, June 1859

Photons are the elementary units of electromagnetic radiation, including light. When we see something, it is not simply because light bounces of the surface of some object; rather, the photons making up the light enter the surface, change electrical charges in the material and stimulate emission of new photons – Democritus, Lucretius, and Holmes were not so far off as they once seemed. Photons can be said to account for the entirety of photography.

In a world in which billions of photographs are produced each year, how might we model the production and use of photographic documents? Could we construct a robust model of documents which functions for photographs as well as print documents, music, and oral poetry? Is there a taxonomy or a functional vocabulary which would enable discussion of the entire range of photocutionary acts?

We have been looking at photographs, their production, and their use for some time. As we contemplated photons striking a surface, changing the energy states of electrons in the material struck, causing the generation of indexical photons, and these secondary photons impacting a sensing device (film or CCD chip,) we were stricken more and more by the “pastness” of photographs. We then began to think of examples of photographs that were obviously not mere windows on reality as a stimulus to thinking about the “pastness” of any photograph; then, by extension, any document.

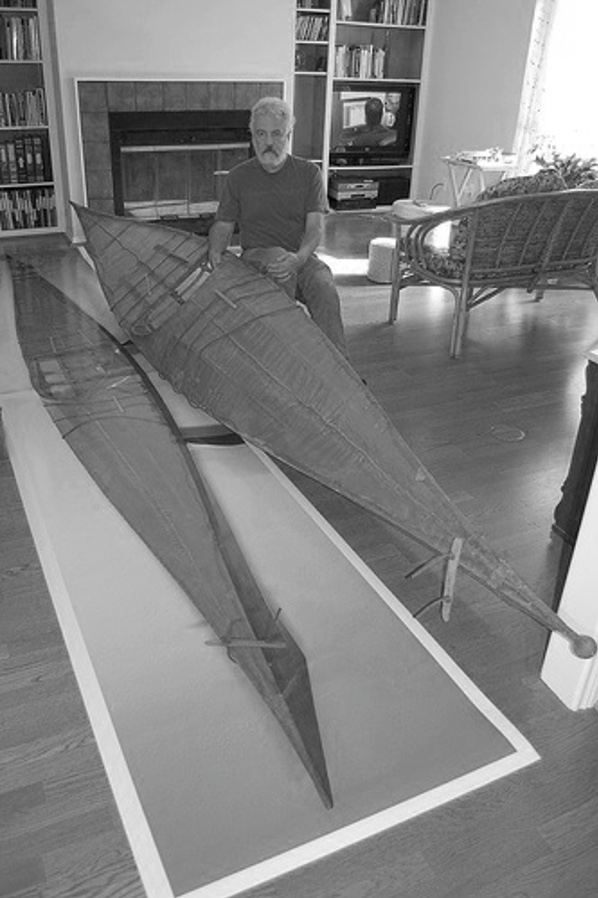

The image of the same man in two different locations and wearing a different hat at each location may seem to be a “trick.” Perhaps, two images have been stitched together. This is, in fact, one photograph made in camera – that is, without any post-production manipulation. The exposure was approximately one and one half minutes long and was made with a scanback recording device. The image was recorded line by line from right to left. After the scan line had passed the point of the man on the right, he ran behind the camera and to the other end – the left end of the boat – while the scan was recording the middle portion of the image. The scan recorded the same man in the second position at about a minute later than the first position. The only “trick” involved is that the recording was not made in the ordinary manner of presenting photons to the entire recording surface all at once. The photograph is a recording of events over time – a two dimensional representation of a four dimensional event.

Here an image made in one eleventh of a second shows us a variation on the same theme. The image data was laid downprogressively rather than all at once. The camera was attached to a kayak on choppy water, so that during the time of theexposure it went from the crest of a wave to a trough to a crest. The relative position of the camera to the shoreline changed along a wave function. The photograph gives us a representation not only of the objects, but of their changing spatial relation to the camera over time.

Here, a photograph made in a more ordinary (snapshot) way has been altered within Photoshop with the application of a charcoal filter. The original recording has been altered to represent the photographer’s engagement with the event and the recorded document of the event.

Let us consider pictures. Or, rather, let us consider photography. Or, perhaps more usefully, let us consider acts that we characterize as photography. How do we define the boundaries? What relates solar / shadow imaging to hyperspectral digital photography? Let us draw the boundaries of photography as widely as possible, both in the regime of intent and the regime of analysis. We then assert: Photography == Light goes in, and then Light comes out. More specifically, information about the photons present in a region of space and region of time is in some way carried through time or space and allowed to “live again” in a manner that exceeds our expectations for how light behaves when it is not manipulated.

So, what traits does a photon have? Direction of travel, location, wavelength (polarity too…), intensity / flux and its variation with time and space. The manner in which these characteristics are mapped from the input photons and light volume to the output photons and light volume encompasses the entirety of photography.

Let us now move in another direction to see if we can shed light from a different angle. Grant us one assertion: photocutionary acts are acts of documentation. Wait, what is documentation? Let us step away for a moment from intent, consciousness, intelligent actors, and even “action”, and attempt to build a partial model from the minimal case.

If we think about photons, we realize that they come from some place at some time and in the making of a photograph they (or their lineage) present a past state of affairs. We might then propose that photographs and perhaps documents in general are mechanisms that resolve the past or predict the future in a universe that makes both acts seemingly impossible.

Let us be more precise. For the purpose of exploring some conceptual boundaries we may become quite reductionist. In no way, however, do we assert that instantiations of complex entities should be understood, contemplated, appreciated, or interacted with based on the following treatment.

Consider a totally closed, totally deterministic system, and impose the passage of time. The system will evolve in some way that depends entirely on its initial state. Impose the concept of an observer outside of the system: an observer with perfect knowledge of the system’s initial state can perfectly predict all future states of the system. This means that the information content of the system is unvarying – one is able to fully represent the system at any time by specifying the initial state of the system and an amount of time.

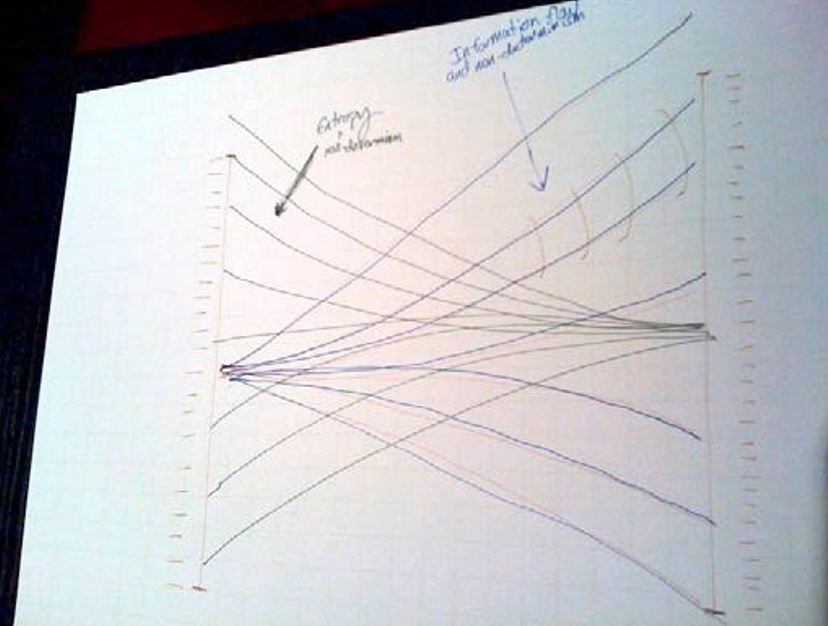

Does this mean, however, that by observing at a given time after the initial state an observer can determine the past?No. Entropy is (with apologies to pharonic self- description) the arrow of time, destroyer of order, and, consequently, the concealer of the past. Entropy is best understood as a measure of how difficult it is to determine a system’s past state from its present state. Also, the increase in entropy that occurs due to a process is a measure of how hard it is to reverse (or simulate the reversal of) that process. Entropy arises entirely due to the fact that any given present state can have been arrived at through any number of different pasts, as modeled below.

Note that this means that a hypothetical universe in which every particle carries along a history of its state through time has no tendency towards increasing entropy! AND, perhaps more relevantly — in our universe things _do not_ carry an explicit history. Their present state is dependent on their history, but no single history is unique to a given state. A system which moves forward in a totally predictable way but which is not guaranteed to reveal any of its past.

In fact, we know that within the confines of the universe it is impossible to find such a system. So let us place our system and our observer within the universe, still leaving the observer outside of the system, and let’s make the boundaries of our system transparent to information (that is, we allow communication). As far as we know, in our universe information flows in one of only five ways: through changes in gravity, electric fields, magnetic fields, and fields of the strong and weak force. Information is the contribution that a given subset of the universe makes to those fields. Communication, then, is influence, and influence is communication. We say two entities are in communication if some aspect of entity 1 has any influence over entity 2.

Let us observe an initial state, let some time pass, and observe a second state. What do we find? The observed second state – state at time 2 – does not match the predictions of the observer. Why? Five reasons, only two of which are relevant to our discussion:

- Initial state measurement error – includes both errors of measurement and the effect measurement has on the system

- Final state measurement error – includes only errors of measurement (systematic or limited by fundamentals (Heisenberg etc))

- Deficiencies of prediction (inaccurate or incomplete model)

- Non-determinism (whether viewed as probability distributions of wave functions or as ignorance of which of many universes the observer is in)

- Information flow through the boundary of the system

Let us simplify things here by ignoring 1 through 3 – we assume an observer who can perfectly measure the state of the system at any time without affecting it, and who possesses a perfect model of the laws governing the evolution of the system. This also serves to eliminate the effect of strong sensitivity to initial conditions (chaos).

So, from the perspective of our observer, something is acting to derail the system from evolving in the manner expected, and the measurement of the system in its final state will be a surprise. This means that to keep the model in sync, the observer must update it with newly observed values, which represent transfer of information from the system to the observer.

However, the non-determinism inherent in the system is not totally random — its distribution is in fact a characteristic of the physical laws governing the behavior of the system, thus a perfect model of the system would generate an infinite number of end states, each associated with a probability. Thus, a present state that lies within the bounds of what is possible under the expected non-determinism is, in fact, only surprising to the extent that the outcome lies far from the median value of expected states. Thus we can say that the non-determinism itself is not actually generating information, and that information crossing the boundary of the system has affected the system or imparted information only to the extent that it pushes the observed final state toward the tails of the expected state distribution.

Now let us step back for a moment and consider the source of all of this information flowing into the system. It is coming from changes in the universe outside of the system and their influence on components of the system. We can say changes because we assume that the observer takes into account the external influences present at the initial state; or in the absence of an observer, the presence and intensities of those influences is, in fact, a trait of the system and is not distinct from it, and should properly be included in the information count at the initial state.

So, let us say that our observer, accustomed to a system that consistently behaved according to the probability distributions as modeled (before we let information in), starts observing a significant departure from expectations and decides to investigate. After some contemplation, the observer arrives at the idea of varying external influences. The observer contemplates a while longer and quickly despairs, realizing that simply measuring State 2 can never reveal how the external influences changed during the time between State 1 and State 2. This is true for the reasons mentioned before: non- determinism and the concealer of the past, entropy. To clarify: non-determinism means that any particular State 2 could just be the result of a particularly unlikely unfolding of events since State 1 (the quantum mechanics idea of everything being possible, just very, very unlikely). However, for large systems (containing “lots” of wave functions, and there are 10^many in a tiny tiny grain of sand), significant departures from the mean are extremely unlikely. This means that the observer can fairly safely model the information that has flowed into the system as a transformation of the probability curve with the observed state lying at the mean (and a super-observer who could run the universe back and watch it unfold bazillions of times could observe the departure of the outcomes from the predicted probability distribution) (See here entropy figure above).

This distance between the predicted distribution of outcomes and the observed distribution of outcomes is a measure of the net information flow into the system during the time from State 1 until State 2, and the minimal representation of the difference in shape and position of the curve _is_ the information transferred. It is not the magnitude of difference of individual possible states from their uninfluenced counterpart that matters, but the minimal representation of the difference in the distribution of possible states.

So we can say with some precision how different the system is from what we expected it to be, but our old entropy/irreversibility friend is still around, and the system could have traveled any number of different paths to get to the present, with any number of combinations of external influences having played a role during the evolution of the system. This leaves the observer unable to make strong statements about the state of the system or the external influences acting on it at any time between Time 1 and Time 2.

The observer is even further constrained. Even if it were possible to determine exactly how the incoming influences (information) had varied with time, they do not represent a unique configuration of the rest of the universe. This is analogous to the entropy problem and time… The further some part of the universe lies from the system, or the smaller its contribution to the influence field, the less able the observer is able to make strong statements about it. Here we arrive at the connection between this thought experiment and our own experience with communication and documentation.

Documentation

Here we say that documentation is a phenomenon of communication wherein the blurring that occurs with time and distance due to the phenomena outlined above is significantly less for a given communication than would be expected given a naive understanding of the entities involved, and a documentary act is a change in the configuration of the entities involved. That is, when communication occurs, the evolution of state of some part of the universe is changed due to influence from another part of the universe. The degree to which small differences in state of the part doing the influencing are reflected in unique, discernibledifferences in state of the influenced part beyond what would be predicted based on their separation in time and space is a result of the documentary nature of the communication. Thus, if we regard the influencing and influenced entities and all of the intermediary entities as a single system, we can view a document as a wave of local entropy reduction which travels from the distant past influencing region to the near/present influenced region, representing a trajectory of enhanced reversibility that couples the past and present, maintaining coherence of information.

So, another way to think of a document is to ask what sort of resolving power does a document afford one in determining a past state? A photographic document presents a means of recovering the vector state of the past that is more useful – enables a closer mapping – in some situations. There exists the possibility of recovering from the initial files, the temporal, spatial, and spectral component(s) of some State 1 from the State 2 represented in the photograph. As one possible example, consider the word “greave.” For most people today this is not a sufficiently common entity in daily life for the single word to bring to mind or use, say, the 3-dimensional shape of the entity. Even a passage from Homer may not be sufficient to do so:

Homer, The Iliad (ed. Samuel Butler) book 21, line 590:

As he spoke his strong hand hurled his javelin from him, and the spear struck Achilles on the leg beneath the knee; the greave of newly wrought tin rang loudly, but the spear recoiled from the body of him whom it had struck, and did not pierce it, for the gods gift stayed it. (6.16)

A standard 2-dimensional photograph may present a closer mapping between the document and the original entity or state. Stereographs from the 19th century and various 3- dimensional imaging systems today are capable of even closer mapping between State 1 and State 2. There is, of course, a wrinkle in our representation. The photograph is not from the time of Homer; rather it is from a modern reproduction of a Homeric tale. The greaves in the movie were constructed by one to one mapping from ancient greaves to modern reproductions – in themselves, then, a form of document.

Similarly, we have photographs of gullies on Mars. Gullies on Mars are not coded by humans. They exist as the result of laws of physics operating over time. Humans participate in coding by lens design, sensor design, transmission system design, and target selection. In many ways the photographs of gullies on Mars are like snapshots of a birthday party, in that both select surface structures to record for future use.

A photograph made of a butterfly on a planet in the Vega star system would not be a document on Earth because it would be too far away to interact with an entity on Earth. Even if residents of Earth had received a notice that a photograph would be made on some particular date at a Vega butterfly colony and sent at the speed of light on that date toward Earth, it could have no impact on an Earth resident for about 25.3 years. Now, it might be argued that knowing a Vega butterfly image was on its way might impact an Earth resident, but that impact would be only from the initial notice that such an image document would someday be on the way.

Photons In, Photons Out

Our consideration of the movement, capture, and display of photons leads us to modeling photocutionary acts and howwe might think of them as resolving the past. During the pre-capture of data stage decisions are made about just where to aim the capture devise, what sort of time frame would be appropriate for the capture, whether the capture should be “artless” (see Vince Aletti, “Mail of the Species” New Yorker, March 16, 2009, p. 27) or artful – here think of NASAhigh-resolution imaging of shuttle parts to look for stress fractures vs. gauze filters to smooth imperfections in a “romantic” portrait; and issues of lighting. At the capture stage the mechanics of what sort of lens would be ideal (focal length, maximum aperture, linear distortions, chromatic distortions, price, and time required) are combined with determining tradeoffs of expense, rigging, intrusion on the subject (one would likely not set up a high resolution imaging system that requires a five minute exposure to record a child’s birthday party; nor would one propose making official museum records of holdings with a cell phone camera.)

At the post-capture stage issues of changing brightness, tone curves, contrast, unsharp filtering, and numerous other manipulations are weighed against issues of verisimilitude: legs made “perfect” for an advertising campaign by lengthening; eliminating distracting elements from a cover photo for a national magazine; Photoshopping out a piece of lettuce in the smile of a faculty website portrait. At the publication stage technical decisions about the quality of printing, color management, storage space, and simple size of the displayed image are weighed against issues of utility, cost-to-gain ratios (a three by twelve foot print of the Very Large Array might be the perfect image to enhance a conference room, but the several hundred dollar cost of just mounting the print, instead of tacking it to the wall, is not trivial.) Re-use of images raises issues of whether they ought to be displayed in a different size or format than originally intended. We might ask if display of a digital version of an antique photograph “violates” original intentions. We might ask if a “better” print serves some purposes well, while casting a curtain between the image and what earlier viewers would have experienced.

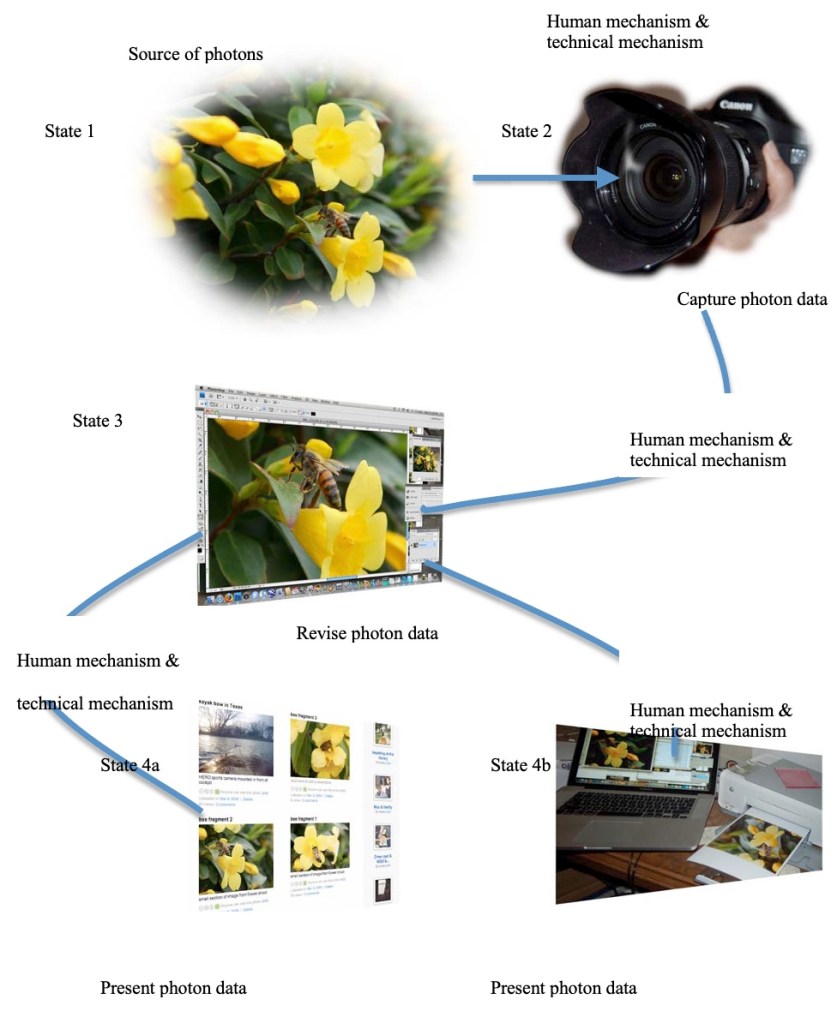

We might summarize this line of reasoning with a model of relationships. This model is a demonstration from which to conduct discussions and elaborations. Source of photons may be taken as State 1; capture as State 2; each post-production editing step as Stage 3a, 3b, 3c …; each display decision or instantiation as Stage 4a, 4b, 4c, …; each access/retrieval decision as 5a, 5b, 5c, …; each re-use activity as 6a, 6b, 6c… We might add that agents at each stage might actively want to know the mechanical and / or the human decision components of previous photocutionary acts. We might note that this wave of coherence through time is instantiated in what would look like individual documents, so we might want to consider Anderson’s notion of document lineages (Doing Things with Information, p. 38.)

Note that following the trail of the mechanical rules for recovery of the past is, conceptually, simple; tracking the human decision making may not be so simple. At every stage each photocutionary act (analogous to Austin’sutterance) has a mechanical and decisional component.

We offer this model as a substructure for discussing photocutionary acts with the rigor that has long been available for word documents. Among the myriad questions at play we might name these few as examples:

- the boundary between image-as-bits and image-as-photons

- photon metadata

- metadocumentation

- extraction of information beyond photographers’ intent

- measuring vs. reproducing vs. expressing vs. …

- telescope image of planet vs. “abstract” print made with no lens

Photographic Representation of Realia

In order to pursue notions of photographic representation, we consider here the use of photographs for representing cultural heritage objects. We do not assert that photographs are or can be the same as the objects themselves; nor do we assert that photographs of even the highest possible degree of verisimilitude could have all the cultural and environmental qualities and connotations of an original. However, we do assert that there are circumstances under which a photographic representation of some sort might well stand in the stead of the original, particularly for uses that might put the original at risk.

We then consider various means by which photographic representations might be made that approached one-to-one correspondence with the original even more closely. Perhaps we might find ways to approach representing some of the affective qualities of the original entity that are often missing from current cultural heritage objects photographs.

Artifacts of cultural heritage can be vandalized, they can be damaged by environmental changes, and they are generally only in one place at a time. Here we see a photograph of a kayak on display with “only a psychological barrier” – a Do Not Touch sign– which was damaged by the foot of an enthusiastic child. Similarly, we see a photograph of damage that resulted from changes in the environment in which it was stored.

Even in its intact state, the kayak was too fragile to be loaned out to just anybody who would have liked to paddle in an antique boat, in the manner that a book would be loaned out. Perhaps more realistically, it was even too fragile to be loaned to scientists for various ethnological studies of stability and trim characteristics of hunting kayaks. (Zimmerly, 1982)

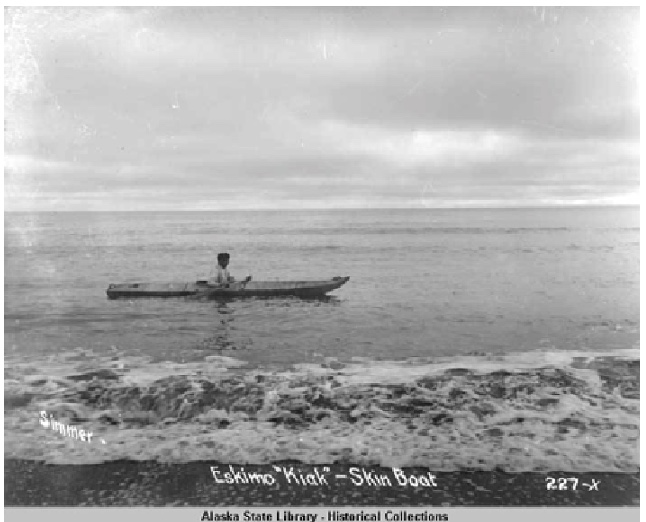

For various reasons, it often makes sense to construct a representation of an artifact. In the case of a kayak, this representation might be a set of words (Library of Congress Subject Headings “Skin boats” and “Kayaks” have been used in museum settings and variants such as “qajaq” and “kaiak” appear in the captions of old photographs); it might be a set of line drawings or a table of measurements at standard points; it might be a full- size replica or a small model; or it might be a photograph.

Here we will use the case of representing a kayak as a case study, a stimulus for how we might think of photographic representation of realia or physical objects, and as a way to gain insights in to representations by looking at tradeoffs. When we select or highlight some attribute of an entity, we necessarily leave some others behind. What we leave behind has impact on how the representation can stand for the “original.” The purpose or application drives the nature of the representation. Conversely, the nature of the representation has impact on what can be done with the representation.

Let us assume that we are considering making a photograph to stand in place of a “real” boat. Let us assume that we are doing this within a museum or archive setting where we might ordinarily have the actual boat on display, likely with some form of barrier of more substance than the “psychological barrier” meant to protect the kayak. We might imagine an arrangement such as that shown here for display of a dugout boat in the Hearst Anthropology Museum at the University of California, Berkeley. Here a post and fabric barrier keep visitors at arm’s length and the orientation of the boat against a wall restricts viewing, essentially, to one half of the boat. On the wall are grayscale photographs that provide context for the boat, along with verbal descriptions of the boat and its provenance, construction, and uses.

Photographic Tradeoffs: Optimizing for Applications

Some photographic tradeoffs are beyond the control of current users of representations made at earlier times. Here we see a photographer at work in Alaska one century ago. While some field photography from that time is remarkable, it is the case that all the images from that time are grayscale; any color was added by hand directly to prints. The camera processes required non-trivial amounts of time and physical effort and light, thus we do not always have multiple images giving all views of an object. We do not always have data on the lens, film size, and other mechanical aspects of the production, so we cannot easily compute or deduce relative sizes, accurate textures, and other significant characteristics of objects of interest. ome tradeoffs are simply part of the mechanism. At this time most photographs are two dimensional, with the arguable exceptions of videographic representations in which time would be the third dimension and stereographic images that reproduce only a “locked head” three-dimensionality. Most photographs do not weigh the same as the objects they represent, nor do they present the smell of the original object.

Because photographs are exquisitely empirical, they present us with a form of dysfunctional rightness. That is, we are presented with one very specific data set from a very specific set of circumstances. In this photograph of an “Eskimo ‘Kiak’” we cannot tell if the boat is in motion, heading toward or away from shore, at what time of day the photograph was made, or how well the hydrodynamics of the boat are suited to the particular body of water. These are neither good nor bad, they are simply aspects the photographic representation process.

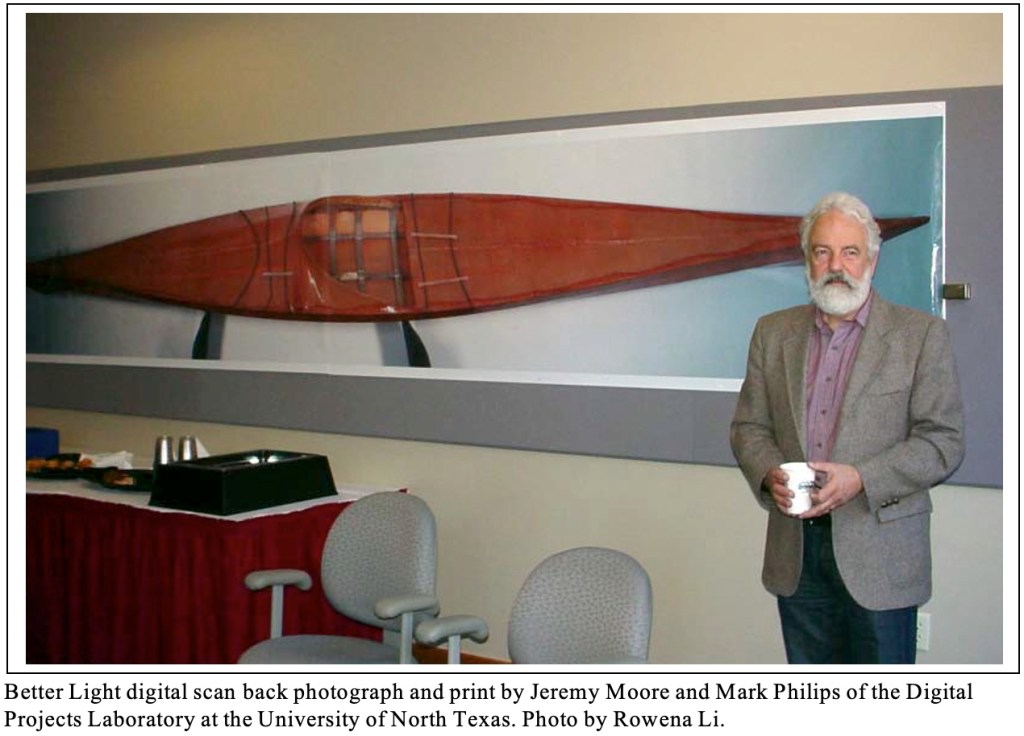

Ultra-High Resolution Photographic Representation of Realia

There is a commonsense surety to an assertion that the higher the resolution of a photograph of a museum object, the closer the representation approaches a 1:1 correspondence of object attributes to representation attributes. Surely there are numerous situations in which a high-resolution image can act as a surrogate for the “real” object. We argue that the close to 1:1 correspondence is significant, since it can often be achieved with expenditure of fewer resources than would be necessary to maintain the “real” object under similar conditions of use. There are, however, other issues that come into play in considering the relationship of a photographic representation to the “real” object.

If we assume an object is made up of some set of attributes |A|, degree of verisimilitude might be taken to be the proportion of attributes manifest in the representation divided by the total set: a1, a2, a3…an/A. In practice there might be some difference. If we were only concerned with the visual stimuli (as in the case of what a museum patron would see if there was a barrier that kept the kayak four feet from patron eyes and hands and feet), then our total set of attributes of the object would be smaller. We might be able to come close to a 1:1 correspondence between the visual attributes of the object and the visual stimuli from the photographic representation.If one stands at the same angle to the photograph as the camera that made the photograph and looks through one eye, the data set from the high-resolution image and the original kayak are essentially the same.

To determine the minimum pixel count required to produce an image that matches human visual acuity at a given viewing distance, we must start with the angular resolution of human visual perception. Characterizing this trait is quite subtle, but we can productively proceed from a familiar source. Snelling(1) found that we may roughly treat typical human vision as capable of discerning high-contrast content at a spatial resolution of 1 minute of arc. In fact, Snelling notation (the familiar “20/20” form) is defined such that the inverse of the ratio gives the resolution in arc minutes. Proceeding from this, we can determine that the width of a minimally-resolved object at 1 meter is 2 * tan (.5′)m, or .29mm.

From the Nyquist sampling rate, we know that to reliably resolve and reproduce such an object, we must sample at twice the resolution we wish to reproduce for display, and accordingly our imaging must be performed such that each square pixel maps to a region .145mm across. From here we may proceed directly to the pixel count: the required pixel count is simply the area of the print over the area of these per-pixel regions. For the kayak image in question, this comes out to (32.5inches * 16ft) / (.145mm^2) = 190megapixels. This corresponds to a print resolution of just over 170dpi. Especially if we consider the color and contrast ratios of most objects, these figures of resolution are within the capabilities of current ultra-high resolution digital imaging systems (e.g. Better Light Super 8K at 216 megapixels or the 10K HS at 384 megapixels.) Thus, we may say that we can now produce a photograph of a kayak that is the same size and presents to the viewer’s eye essentially the same data set as would the original. That is, as shown in the image here, we can achieve a 1:1 ratio at full scale.

Behavior, Senses, and Representation

If one stands at the midpoint of a 16-foot boat and looks to one end, it is difficult to make out the details at the ends; so,one might walk two or three paces toward an end and give it closer examination. The same holds true with a 16-foot photograph of that boat; if one stands at the midpoint of the photograph there is a similar amount of difficulty in making out details at the ends. This adds back into the representation and viewer engagement with the representation the haptic element of coming to “know” the length by operating within “lived world” attributes – it is about three paces from the middle to the end.

However, if one does walk toward the end of the “real” boat, one is presented with a new set of data; while, if one walks to the end of the photograph, it may be easier to make out details, but the data set is the same. For illustrative purposeswe might posit a Central Axis of Representation. In most photographs there is a single Central Axis of Representation. In the case of our kayak, the camera was placed so that a line running perpendicular to the image sensor and through the center of the lens would transect the kayak just at its midpoint. Looking with an eye placed at the same point would produce a data set essentially the same. We say “essentially” because even with rigorous color control procedures in the production of the photograph, different eyes have different distributions of color receptors. Moving the eye to the end of the real boat shifts the eye’s Central Axis of Representation to a point, say eight inches from the end; moving the eye to the end of the photograph does not ordinarily bring about a shift in the Central Axis of Representation of the real boat, though it does do so to the photograph of the boat.

Consider an observer’s behavior when they first encounter an object (whether part of a representation or not). There is some part of their behavior that can be described as novelty-driven or perhaps even novelty seeking. That is, there’s a substantial part of their behavior which is modulated according to what aspects of the object are novel, whether individually or when considered in the context of the object, the setting, or the time (that is, how recently the observer has encountered such aspects).

Accordingly, one measure of the fitness of a representation is the degree to which encountering the representation reduces novelty-modulated behavior upon subsequent exposure to the object being represented. There are a number of details we haven’t considered here, including the fact that the representation may be so application-focused that it can succeed without reducing the novelty of the object itself. For example, a representation meant purely to convey information about the size of a shipping container required for a kayak would probably not significantly reduce the novelty of interacting with a kayak later, unless one initially had no preconceptions about the size of a kayak. If you expected, for example, a kayak to be one foot long, then receiving a representation of the container stating: “17′ x 3′ x 2′” would strongly reduce one’s novelty response upon observing a kayak.

This leads to the sensory modality fusion issues and non-conscious behavior issues, specifically the co-evolution (or co-design for manufactured observers) of both sensory systems and the specialized cognitive mechanisms fed by those sensory systems. The cognitive processing equipment evolved with the simultaneous presence and input of many sensory modalities, and our intuition about how best to induce a specific observer state with a representation may serve us poorly if there are strong inter-modal fusions occurring in the cognitive process.

Sensory input includes proprioception, so as an example there may be priming or biasing of the visual system that occurs according to limb position and “heft” (which we use here to designate the complete set of information obtained through hefting… encompassing information about hidden moving parts, angular momentum/mass distribution, weight, deformability/solidity, etc.). Likewise, there may be strong perceptive and cognitive effects due to smell signals… and there are certainly very strong effect on memory from smell effects and sound effects. These examples are of course the most concrete and simple cases; the range of effects most likely includes some which are much more subtle, multi-dimensional, and profound.

Another way to put this is that we cannot simply enumerate aspects of an object that are removed or distorted by a representation when considering the impact of the representation on perception and cognition by the observer. Depending on very specific cognitive details of the observer there are strong per-object/object class, per-feature, and per-task impacts on the interaction of the representation and the observer.

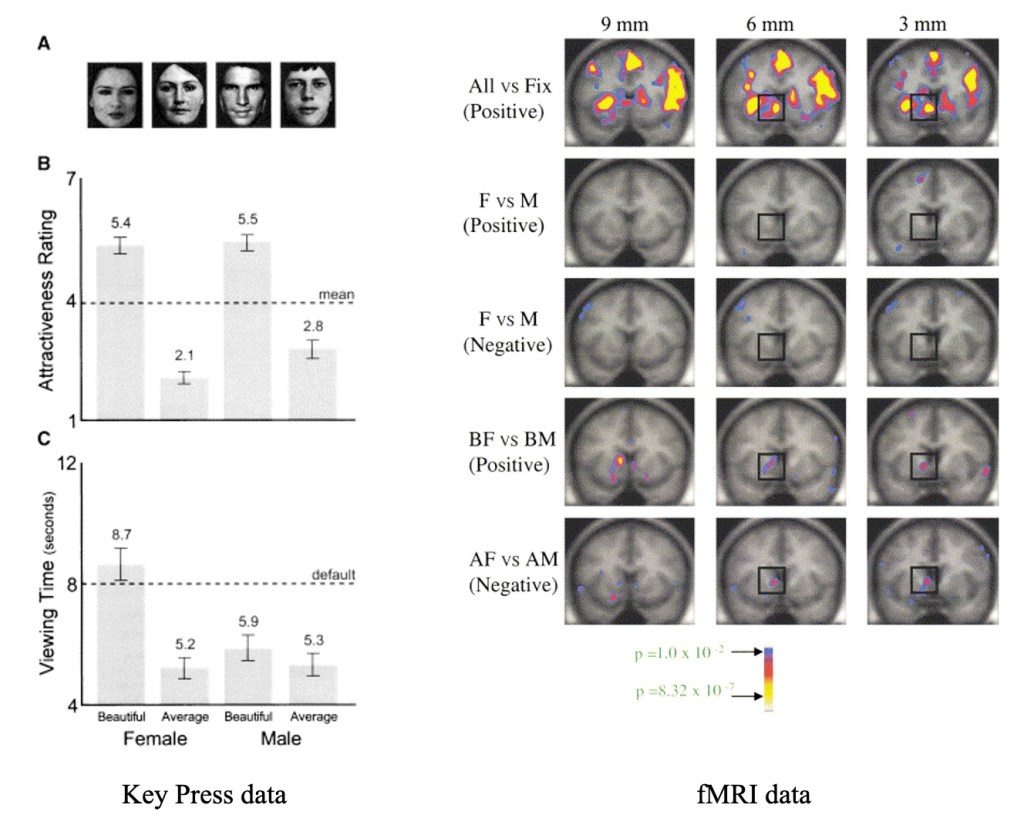

Fusion of visual and broadly haptic might be represented by the fMRI imaging of the impact of low-resolution images of women’s faces on heterosexual males. Faces judged attractive held attention longer and activated reward centers in the brain. We could, to put it rather simply, engender emotional response in a non-emotional setting. We are not suggesting that we want viewers of photographs of kayaks to become “turned on,” though we are suggesting that the beautiful faces research suggests that more is at play in viewing high-resolution photographic representations than the mere inputting of visual data.

In research published in 2001 by Aharon, Etcoff, Ariely, Chabris, O’Connor, and Breiter, it was shown that:

...the brain circuitry processing rewarding, and aversive stimuli is hypothesized to be at the core of motivated behavior. In this study, discrete categories of beautiful faces were shown to have differing reward values and to differentially activate reward circuitry in human subjects. In particular, young heterosexual males rate pictures of beautiful males and females as attractive but exert effort via akeypress procedure only to view pictures of attractive females. Functional magnetic resonance imaging at 3 T shows that passive viewing of beautiful female faces activates reward circuitry, in particular the nucleus accumbens. An extended set of subcortical and paralimbic reward regions also appear to follow aspects of the keypress rather than the rating procedures, suggesting that reward circuitry function does not include aesthetic assessment.

The data for the keypress behavioral experiments and for the functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging experiments are summarized below. We present this data to suggest that different forms and uses of photographic representations might benefit from current research on the visual component of engagement with photographs and the potentially significant contributions (or blockage and confusion) of other brain / body components to the perception of the image.

Data Compression and Representation

In both audio and video compression there has been considerable work put into systems that can quantify the degradation of an input signal by the compression process. It was realized fairly early that one cannot simply measure the error present in the lossy compressed version of a file and use that as a measure of the quality of the compression, because the “quality” is a characteristic of perception and cognition, not merely directly measurable characteristic of the file alone. Both .mp3 and recent video compression schemes use q-measures or quality measures which depend on psychoacoustic or psychovisual modeling to evaluate the degradation. So far these systems are very basic and empirically derived rather than being based on rigorous models of the human perceptive/cognitive system, yet they are interesting to consider.

An example is 2-pass encoding, wherein the compressing program is given an input file and a specification for howlarge the output file should be. This means that the bit count available per frame is fixed at “total size budgeted “/ “length of input file”. However, we can see that different parts of an input file may need more or less data to be represented with acceptable visual quality. Accordingly, the compressor will run through once compressing the entire file at the bit rate specified, and then evaluate the “quality” of sections of the resulting file. Sections whose quality has been degraded more than the average will then be recompressed at a higher bit rate, and sections whose quality has suffered less (meaning lower complexity, by some measure) will have bits taken from them and reallocated to other sections.

Again, the skill with which a compression program can do this is heavily dependent on how well it can algorithmically determine “quality”… and this is something that gets to the heart of the issue of representation, clearly!

We might imagine a kayak photograph viewing system using a related approach. Suppose you could have an eye tracker that could tell where on an image a person was looking and link that vector to a re-assignment of the number of bits to that portion of the image. We might store all the data and do the re-assigning on the fly or store a set of index files that would have the center of the image, other highlights, and one or two background elements at high resolution and then the system would just shift which file was being shown.

We must recall that under ordinary circumstances of making and viewing prints, there is a distinct difference between walking to the end of a real kayak and walking to the end of a full resolution and full size photograph; the angle of view is different. The photograph will ordinarily have been made with the camera axis in line with the midline of the boat. So that when one views the photograph while standing at an end of the print, the data presented to the eye is still from an angle at the midline of the boat. This is not necessarily a negative aspect of the representation, but is something that must be kept in mind.

Now, given the ultra-high resolution and the characteristics of lens and the image capture apparatus (e.g., three head, line-by-line scanner) one could imagine calculating offsets from the Central Axis of Representation of the original recording. Similarly, one could imagine making multiple images from multiple axes along the length of the boat and playing back the image taken from the vantage point at which the viewer happens to be standing at any particular viewing time.

Of course, we could then say that a human observer of the original kayak could likely move up and down with respect to the object; indeed, they might be able to (or wish to) have 360-degree coverage. There is no conceptual difficulty in constructing a photographic representation system that would accomplish such changes in the viewer’s Central Axis of Representation other than the computational power to make seamless adjustments of the ultra-high-resolution images.

Closing Thought

Oliver Wendel Holmes writing of stereophotography in the mid-19th century spoke thus of the representational power of photographs:

The very things which an artist would leave out, or render imperfectly, the photograph takes infinite care with, and so makes its illusions perfect.

Photography is a powerful form of representation. As resolution and color management capabilities increase, we approach a 1:1 correspondence with the external surfaces of objects. The representation task may now include means by which we achieve greater correspondence with other attributes. A perfect representation (illusion) is a difficult concept to define; however, increases in imaging technology push and enable our abilities to refine the nature of photographic representation to suit more purposes.

References

Aharon, I., Etcoff, N., Ariely, D., Chabris, C.F., O’Connor, E., Breiter, H. (2001). Beautiful Faces Have Variable Reward Value: fMRI and Behavioral Evidence. Neuron, vol. 32, pp. 537-551.

Greisdorf, H., O’Connor, B. (2002) “What Do Users See?” Proceedings of the 65th ASIST Annual Meeting, 39: 383-390.

——- (2002) “Modeling What Users See When They Look at Images: A Cognitive Viewpoint” Journal of Documentation, 58(1): 1-24

Marr, D. (1983). Vision: A Computational Investigation into the Human Representation and Processing of Visual Information. San Francisco : W. H. Freeman

O’Connor, B., Anderson, R. and Kearns, J. (2008) Doing Things with Information: Beyond Indexing and Abstracting. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited.

Snellen, H. (1862). Scala Tipographica Measurae Il Visus (Utrecht) Zimmerly, D. (1982). Stability and Trim Characteristics of Native Watercraft:

A Computerized Simulation Study. 1982 CESCE Annual Meeting.

http://www.arctickayaks.com/PDF/Zimmerly/Stability1982/stability.pdf

Photographs of damaged kayaks are from the Canadian Museum of Civilization; antique kayak photographs are from University of Alaska Museum of the North; photograph of Better Light image and Dr. O’Connor by Rowena Li..

Authors

Brian C. O’Connor, Ph.D. University of North Texas

Ethan M. O’Connor, EOCYS

Brian C. O’Connor is a professor in the College of Information at the University of North Texas. His primary research areas include issues of production and use of photographs, idiosyncratic information seeking, and representation of questions and documents.

Ethan O’Connor is an entrepreneurial researcher expanding the domain of traditional signal processing techniques into novel applications.

Leave a comment