In 2009, we were working on a project with imaging engineer Ethan O’Connor for a presentation on ultra-high-resolution photography of museum objects; we constructed the following considerations and model. Note that it was Ethan who commented: “All of photography can be summed up as photons in, photons out.”

In June of 1859, physician, essayist, and photographer Oliver Wendell Holmes (1859) wrote in the Atlantic Monthly that photography provided humans a “mirror with a memory.” We could now, for the first time, have direct, indexical representations of the world about us that would remain fixed across space / time. We have 5,000 years of practice thinking with graven words but less than two centuries of practice thinking with pictures, both still and moving. Now that the means of production and viewing are simple and widely affordable, we find ourselves able to practice new ways of thinking in, with, and about photos. Plato argued that words were useful because they were stripped of specificity; Holmes argued (as do we) that images are useful precisely because of their specificity.

Videos return us to the specificity of lived life.

Let us consider pictures. Or, rather, let us consider photography. Or, perhaps more usefully, let us consider acts that we characterize as photography. We assert: Photography = Light goes in, then Light comes out. More specifically, information about the photons present in a region of space / region of time is in some way carried through time / space and allowed to “live again” (Holmes’ phrase) in a manner that exceeds our expectations for how light behaves when it is not mediated.

So, what traits does a photon have? Direction of travel, location, wavelength (polarity too…), intensity/flux, and its variation with time / space. The ways in which these characteristics are mapped from the input photons and light volume to the output photons and light volume encompasses the entirety of photography. Photons come from some place at some time and in the making of a photograph they (or their lineage) present a past state of affairs. We might then propose that photographs and perhaps documents in general are mechanisms that resolve the past or predict the future in a universe that makes both acts seemingly impossible.

Another way to think of a document is to ask what sort of resolving power does a document afford one in determining a past state? A photographic document presents a means of recovering the vector state of the past that is more useful than words —enables a closer mapping—in some situations. There exists the possibility of recovering from the initial files, the temporal, spatial, and spectral component(s) of some State 1 from the State 2 represented in the photograph. A standard two-dimensional photograph may present a closer mapping between the document and the original entity or state. Stereographs from the nineteenth century and various three-dimensional imaging systems today are capable of even closer mapping between State 1 and State 2. We have photographs of gullies on Mars. Gullies on Mars are not coded by humans. They exist as the result of laws of physics operating over time. Humans participate in coding by lens design, sensor design, transmission system design, and target selection. Photographs of gullies on Mars are like snapshots of a birthday party—both record surface structures for future use.

Photons in, photons out

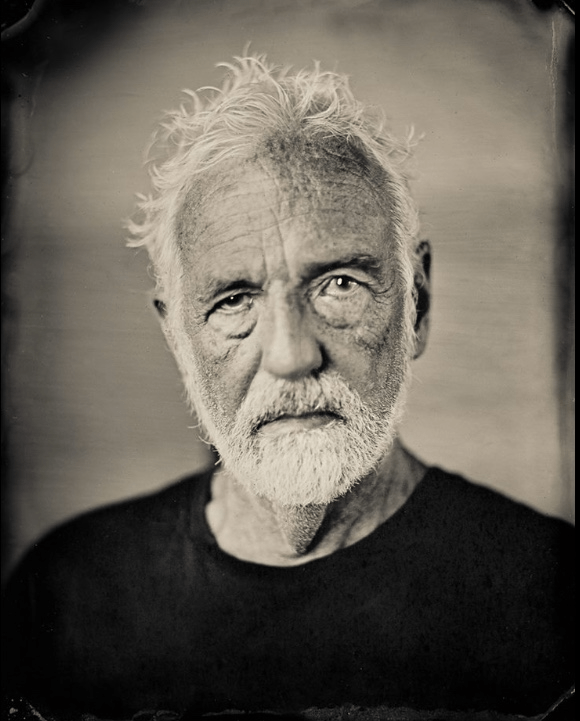

Our consideration of the movement, capture, and display of photons leads us to modeling photocutionary acts and how we might think of them as resolving the past. During the pre-capture of data stage, decisions are made about just where to aim the capture devise, what sort of time frame would be appropriate for the capture, whether the capture should be artless or artful—here think of NASA high-resolution imaging of shuttle parts to look for stress fractures vs. gauze filters to smooth imperfections in a “romantic” portrait—and issues of lighting. At the capture stage the mechanics of what sort of lens would be ideal (focal length, maximum aperture, linear distortions, chromatic distortions, price, and time required) are combined with determining tradeoffs of expense, rigging, intrusion on the subject (one would likely not set up a high-resolution imaging system that requires a five-minute exposure to record a child’s birthday party; nor would one propose making official museum records of holdings with a cell phone camera.)

At the post-capture stage issues of changing brightness, tone curves, contrast, filtering, and numerous other manipulations are weighed against issues of verisimilitude: legs made “perfect” for an advertising campaign by lengthening; eliminating distracting elements from a cover photo for a national magazine; Photoshopping out a piece of lettuce in the smile of a faculty website portrait. At the publication stage technical decisions about the quality of printing, color management, storage space, and simple size of the displayed image are weighed against issues of utility, cost-to-gain ratios (a 3 x 12 foot print of the Very Large Array might be the perfect image to enhance a conference room, but the several hundred dollar cost of just mounting the print, instead of tacking it to the wall, is not trivial.) Re-use of images raises issues of whether they ought to be displayed in a different size or format than originally intended. We might ask if display of a digital version of an antique photograph “violates” original intentions. We might ask if a “better” print serves some purposes well, if a “better” print serves some purposes well, while casting a curtain between the image and what earlier viewers would have experienced.

This line of reasoning yields a model of relationships. This model is a demonstration from which to conduct discussions and elaborations. Source of photons may be taken as State 1; capture as State 2; each post-production editing step as Stage 3a, 3b, 3c …; each display decision or instantiation as Stage 4a, 4b, 4c, …; each access/retrieval decision as 5a, 5b, 5c, …; each re-use activity as 6a, 6b, 6c… We might add that agents at each stage might actively want to know the mechanical and / or the human decision components of previous photocutionary acts. ) We describe this trail of the rules for recovery of the past as a “chain of custody”—familiar from archival science and criminal investigations for assuring provenance and protection from fraud. It is conceptually simple, though tracking the human decision making may not be so simple.

At every stage each photocutionary act has a mechanical and decisional component. We offer this model as a substructure for discussing photocutionary acts with the rigor that has long been available for word documents. Among the myriad of questions at play we have thefollowing.

• How are we to envision the boundary between image-as-bits and image-as-photons?

• How do we speak of photon metadata—or do we?

• Can we/ought we to extract information beyond photographers’ intent?

• Are there meaningful differences between measuring, reproducing, expressing, …?

This essay is adapted from our Video Structure Meaning, available from Springer Nature.

Leave a comment