Some thoughts adapted from Structures of Image Collections on two nearly opposite notions of “collection and “structure” in hopes of stretching our notions of those two concepts and photocutionary acts. First, we will consider the movies; then we will consider individual ultra-high resolution still images.

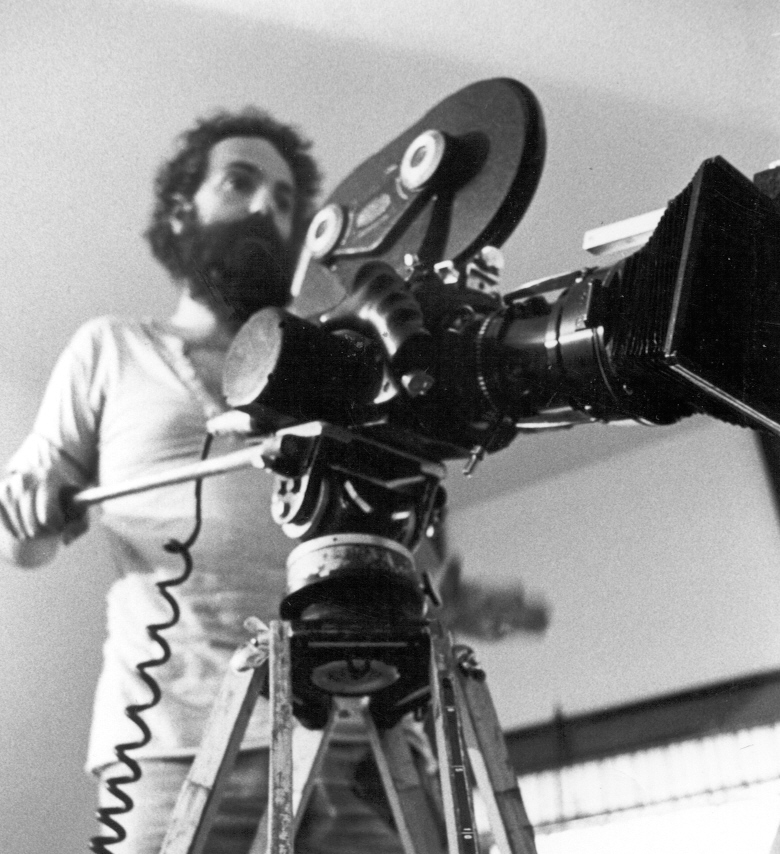

It may be worth noting that this multi-thousand dollar imaging rig could scarcely match the imaging capabilities of a typical smart phone of today. It may be worth noting that this multi-thousand dollar imaging rig could scarcely match the imaging capabilities of a typical smart phone of today. |

Movies arose from a history of entertainment, engineering, and science. They also arose from still pictures. In fact, a movie is nothing more (or less) than a sequence of still images with one primary structuring attribute – presentation of a set of still images to the viewer at a fixed rate. For the video media available these days that rate is generally 30 frames per second. Actually, the presentation rate is sometimes slightly different, say, 29.97 frames per second, to allow for certain housekeeping necessities in maintaining the constant frame rate. This means that every one minute of viewing time is made up of 1,800 still images.

There is no constraint on what those frames should be for any given video, only that they should be presented at 30 frames per second if the illusion of life-like motion is to be maintained. Giving a viewer 1,800 still images, even if they were printed from the frames of the film, would not result in an illusion of motion. In order to be a movie, the bunch of images must be structured in such a way as to be presentable at 30 frames per second. In the illustration here, is a small portion of the frames from a motion picture. All the 12, 803 frames from a 7.1 minute section of the movie are printed on a large sheet of paper. They make for a nice poster and they are not without use, but they are not a movie.

Whether the recording device is a film camera, an analog video camera, or a digital video camera, it is a device that records many still images rapidly. It is not a device that records motion. It is a device that records fragments of motion. In fact, there is a significant amount of time in which it is not recording anything, even when running.

That is to say, this sort collection of images functions as a movie, if and only if playback is made at the prescribed frame rate. The structural element is temporal. Now, this is not to say that the collection cannot be used in other ways. Football coaches have made a significantly different use of movies for decades by violating the temporal element. Stopping the film at the moment a particularly good or bad move was recorded, reversing the film and playing a short sequence over again and again, or moving fast-forward through portions that are not relevant for the particular segment of the team watching the film. Police, athletic coaches, and film theorists all routinely view some portions of film or video footage in slow motion or even frame-by-frame looking for a particular momentary piece of data or a particular discontinuity in the data. High speed recording of numerous frames (perhaps hundreds or even thousands of frames per second) enables playback at very slow motion and, thus, analysis of a large number of data points per second.

On the whole, the filmic collection of frames is structured such that it only functions when played back at a standard rate.

Let us now think about the production and viewing processes to see if we can tease out other structures. Let us look briefly at the film construction process, then at the film viewing process. Here we will use the example of a documentary film on a rodeo. There is no particular reason for this choice, except that documentaries generally fall between the individually produced home movie or artistic piece and the large production team construction of a Hollywood feature.

The filmmaker engages in one or more photocutionary acts. That is, either by pre-planning or by making decisions at the moment of recording, the filmmaker gathers together a collection of images at the rodeo. The content of those images – both topic and production values – will have been guided by the filmmaker’s plan for the collection, as well as by the filmmaker’s understanding of the intended audience. That is, if the filmmaker wants to present the human athletic ability of rodeo riders, then the majority of images in the collection will be constructed to give more frame space to the riders than to horses, clowns, or audience. If, on the other hand, the filmmaker intends an ethnographic study of the rituals surrounding rodeo, then there will likely be many images showing, behind the scenes preparations, audience members reacting to events, announcers, clowns, and all the other participants.

After all the images have been made, they will be arranged. Some of the original images will likely be discarded for poor technical quality, duplication, inappropriateness for the revised plan for the film, length considerations, or any of myriad other artistic and logistical reasons. The filmmaker may choose to leave the images in more or less chronological order or to re-arrange the images to suit the plan of the film. There is no “grammar” of film in the sense of a verbal grammar. There is no analog to the noun or verb. This does not mean that there are no structures to movies; far from it. However, the structures are built on the filmmaker’s understanding of viewer perception. Filmmaker’s learned long ago that structure is a powerful component; they also learned that there is no one-to-one correspondence of filmic structural practices to verbal structural practices. There are some “tried and true” structural practices, such as using “fast” editing to increase excitement. However, there are other methods of achieving excitement and the rapid intercutting of dull or inappropriate images will not achieve excitement.

So, the filmmaker carries out photocutionary acts at the image gathering and image ordering stages. In a general sense, the filmmaker also conducts photocutionary acts at the showing stage by determining the type of recording and distribution mechanisms (e.g., wide release in theaters, showing to a few friends, releasing direct to DVD, etc.) Likewise, the viewer carries out several photocutionary acts. The most evident is the choice to view a particular work. Once upon a time, the collection of movies was limited to whatever came to the local theater. Film viewing was passive at many levels, not the least of which was that the collection came in bits and pieces and did not accumulate (the reels for last week’s film were on their way to another town.) There were in some communities public libraries that had small collections of films, generally of the sort used in schools. Now, of course, it is quite the opposite. Between multiplex theaters in most municipalities, multiple video rental outlets, cable television, video-on-demand, video on the web, and video on numerous personal portable devices the collection of videos is enormous and is no longer ephemeral. So, simply choosing a movie document is now an active photocutionary act.

In the past, watching a movie in a theater or a television show at home was a passive experience in which the images went by in their prescribed order and at the prescribed rate. When the movie ended, that was the end of the viewing act unless one paid for another viewing or waited for re-runs. Now re-runs are easier to find and there is a large array of time-shifting devices and practices. There is also the ability to directly and actively engage in the viewing process. The ability to rewind, speed ahead, play one segment over and over is now no longer available only to producers and a few privileged users (athletic coaches, law enforcement, scientists) whose work enabled them to purchase expensive playback machinery. Videotape, then various digital media have made it possible for virtually any user to view the collection of still images making up the movie in almost any manner they like. For the majority of situations the standard playback rate is still the default mode, but examination and re-examination of individual frames and sets of frames is not only possible but also essentially trivial to achieve.

In either case simple passive viewing or highly interactive viewing, it is the case that photocutionary acts are taking place. In the passive, single viewing it is unlikely that most viewers of a half-hour documentary or a two-hour feature film will recall every image in its prescribed order. Some images will be more striking and more memorable; some will be remembered out of context or out of order; some will likely be mis-remembered. After the viewing, there will be, in effect, another collection of images. This one will be the viewer’s collection, constructed and arranged by the viewer’s individual criteria.

So we might say of a movie that it is, in the most general model, a collection of still images structured first and foremost by the mechanical necessities of reproduction. The actual number of still images is large – 1800 frames per minute of viewing time. Ordinarily, a viewer comes to such a collection to see the whole collection, not simply a few particular images. So, we might say that a moving image document is a collection of images that is intended to be viewed as a single document, so it pushes the boundaries of the definition of a collection – a collection of one.

Leave a comment